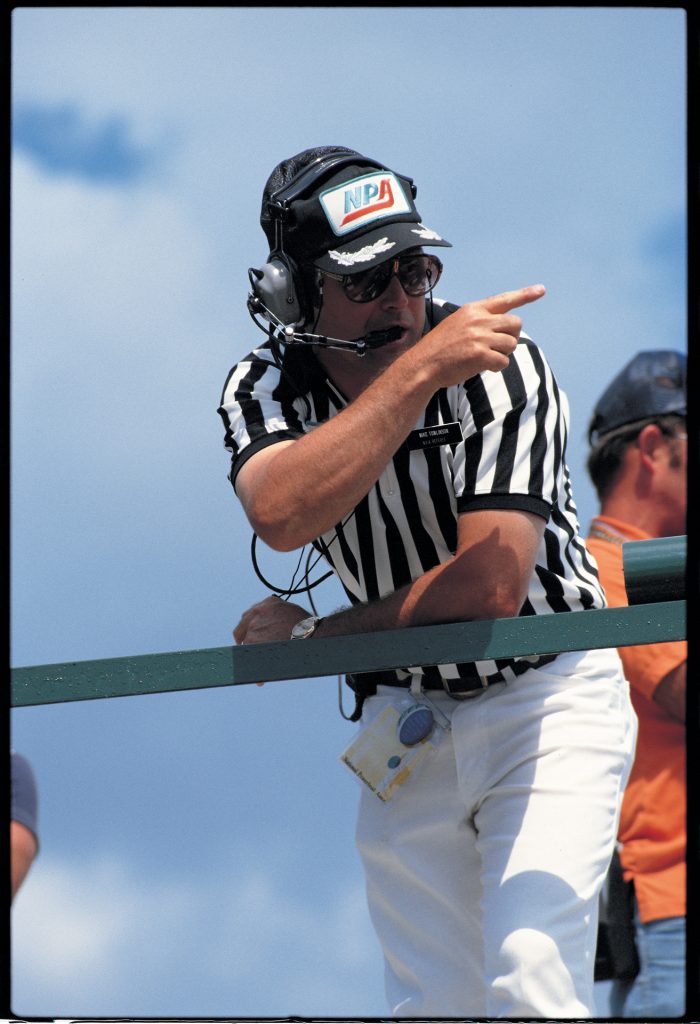

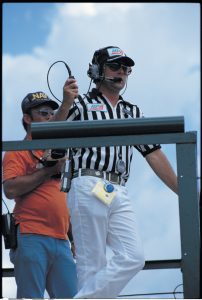

Want to get along with the dean of offshore racing referees, Mike Tomlinson? It’s simple. Just play by the rules

By Eric Colby. Originally Appeared in Poker Runs America 7-3

If you were starting a new powerboat racing organization you’d work hard to lure the big-name teams, try to find attractive venues and make sure you got fans excited. But organizers of the Offshore Super Series, the newest sanctioning body for powerboat racing, wanted another critical ingredient. They needed a top-notch referee to preside over their version of what some feel has been a sport with loosely interpreted rules.

That man is Mike Tomlinson, who, until late February, had been the chief referee for the American Power Boat Association’s offshore division since 1987. That the OSS, which was founded by racers, sought him out means a great deal to Tomlinson.

“I’m very honored that they have asked me to be the chief referee of this organization,” he said. “I hate it for all my friends at APBA, but I need to move forward. From everything I’ve seen, OSS has built a program that’s democratic and fair for everyone involved.”

The 55-year-old Texan has had a history of being firm, but fair when it comes to rule enforcement – and for a new organization, that means members know they cant get away with any funny business.

“They know that I stand for integrity and fairness,” he said. “When you’ve got a situation that demands making a decision among competitors, it’s got to be a fair honest decision and I think they realized that I’m a pretty straight arrow.”

It’s not as if Tomlinson hasn’t already had to answer questions about his integrity. After 40 years in the cotton business, he saw the writing on the factory walls. His company was merging two mills and he was going to be out of a job. A lifelong boater, he got the opportunity to work for one of the premier manufacturers of high-performance powerboats. Now he runs the Eliminator Boats of Texas dealership near Dallas.

“It’s the greatest job opportunity that has ever come along,” said Tomlinson. “I’ve been involved in boats all my life as far as I remember and it’s what I want to do.”

But Eliminator sells boats that compete in offshore racing, which could have created a conflict. Instead of playing favorites with the How Sweet It Is team, which runs an Eliminator 36’ Daytona in APBA action, Tomlinson was extra firm with owner John Peterson and driver Brent Leach (son of Eliminator Boats owner John Leach). They were fined frequently through the 2002 and 2003 seasons for being late for meetings and physicals.

“I was doubly careful to make sure I enforced the rules with Eliminator,” said Tomlinson. “I had a standing agreement with APBA Chief Inspector Paul Abreu. ‘If there is any question about an Eliminator Boat, I would bow out and he would take my place.’”

Tomlinson’s passionate approach to race officiating is equal parts upholding the rules and love for boats. After all, anyone who races loves boats. It’s not as if they do it for the money.

Tomlinson’s affection for the water developed when he used to go fishing with his grandfather near his home in the Dallas suburb of Garland, Texas. “He was a fisherman and had a little outboard motor,” said Tomlinson. “We’d go to the lake and rent a boat and throw the motor on the back. He’d let me steer and, at four or five years old, that was quite a thrill.”

After that, the young Tomlinson was proverbially hooked. On the weekends and after school, he used to ride his bike across town to the local dealership, Taylor Marine, which carried Texasmaid, Traveler and Kingfisher boats and Johnson outboards. Finally, he was offered a job washing and waxing boats. His parents – DeForest, a salesman and mom, Reba, weren’t boaters, but, young Mike had a job working on something he loved. He also had a sister, DeAnne.

“That was my life, hanging around the boat shop and going to the boat races with the guys that hung around the shop,” recalled Tomlinson.

The youngster soon discovered that there were boat races and he used to go to local events with guys from the Mercury dealership across town, Tomlinson still remembers his first event – at Benbrook Lake in Fort Worth, Texas in 1963. “I had a raceboat before I ever had a car,” he said. He bought his own raceboat, a 13’ Yellow Jacket with a 40-hp Mercury. It ran 41mph. Running in the N.D.A. 37-to-40-cid class, he took his share of checkered flags.

Eventually, Tomlinson got hooked up with Abilene Marine in Abilene, Texas. The company carried Johnson outboards and raced with factory support from Outboard Marine Coroporation. Johnny Sanders and Tommy Posey both drove Formula 1 tunnel hulls for the team. Tomlinson became a crewmember, but it didn’t take long before being on the crew wasn’t enough.

Eventually, he stepped up to an Allison Craft with a 65-hp Mercury. That was replaced by a GW Invader that wasn’t as flighty as the Alison. With power from a 100-hop Mercury, it ran about 62 mph. And what did his non-boating parents think about Tomlinson’s running around in 60-mph boats on the weekends during his formative years.

“A lot of this they didn’t know about,” he said. Tomlinson knew he was also quite fortunate in one aspect of racing, saying, “I’ve been thrown out, barrel-rolled and blown over. But I’ve never been hurt enough to be hospitalized.”

Eventually, Tomlinson’s prowess got him noticed and he started driving tunnel hulls powered by 150-hp Mercury outboards for numerous owners in the Sport J Class during the early 1970s. He held two straightaway speed records in the first half of the decade.

But something did slow Tomlinson’s climb through the ranks of tunnel-boat racing. After he got married in 1970, his oldest son Brent was born in 1976. With a family to support, he decided to hang up his orange helmet. Today, Brent and his wife Nikole gave Tomlinson his first grandchild, one-year-old Caroline. Tomlinson has another son, Geoffery, 23, who attends Texas Christian University and works with his dad in the boat business.

With all those years invested in racing and the countless friends he had made, Tomlinson found a way to stay close without getting behind the wheel. He became a referee in the APBA’s Outboard Performance Craft category. He was fortunate to do his apprenticeship under a man whom Tomlinson still considers a mentor, Jim Slack Sr.

“He was a stickler for the rules and his basic advice was be fair, be honest be open and whatever you do, stay by the rulebook and nobody ever questions you,” said Tomlinson. “I try to do it as straightforward and honest as humanly possible.”

Once he became a referee, Tomlinson worked the races through Texas and some outside the Lone Star State, earning a reputation as a fair, honest official. In the early 1980s, he met Duke Waldrop, who was a well-known tunnel-boat racer in the American Motorboat Racing Association, which sanctioned Formula 1 tunnel boat events. Tomlinson worked one of their races before going to serve as referee for the National Powerboat Association, which was based in Huntington, WV.

When Waldrop got hurt in an accident in Nashville, TN, he decided to get out of the cockpit and he and Tomlinson wound up working for the International Outboard Grand Prix, which was the equivalent of the United States’ national sanctioning body for Formula 1 tunnel boats. Waldrop was the race director and Tomlinson the chief referee.

“In IOGP, I was known for ruling with an iron hand and going in there and making calls and having the guts to do it,” Tomlinson said proudly, but without a hint of arrogance. Another man Tomlinson became lifelong friends with was U.S.F.O.R.A referee George May. “We shared a lot of the same enthusiasm for the sport, love of the sport, and I learned a great deal from him,” explained Tomlinson. “The people who’ve helped me throughout life have been fair, open, honest and dead on the rulebook.”

In 1987, Waldrop had become involved with offshore racing through the late Don Pruett, who was organizing an event in Hawaii for the late Tom Gentry. About 20 boats were to go over to the Aloha State for an event. Waldrop said he’d help out, but only if Tomlinson went as chief referee. One of the people Tomlinson met during preparation for the trip was Gene Whipp, who had raced just about everything on water. The two became friends instantly.

After working both styles of racing, Tomlinson switched over fully to offshore in 1987. His first boss was APBA Offshore vice president John Antonelli, who needed help reigning in his sport’s image. “I was hired by John Antonelli to clean it up,” said Tomlinson.

“At one of my first races as an offshore chief referee I shook hands with a whole bunch of cash,” he said. “The cash was still there when I pulled my hand away.” Of course, he refused to identify the person holding all that cash but, given the sport’s colorful past, there’s a host of likely candidates.

Since then, Tomlinson’s been through a host of different personalities at the helm of the offshore division, including Stan Fitts, Mike Jones, Jim Brown, Whipp and, most recently, Michael Allweiss.

“I survived as chief referee for APBA Offshore longer than any other chief referee,” said Tomlinson. “A lot of times I wrestle with the decisions, but I always try to keep the rulebook close my heart and make the decision that’s fair to everybody. I don’t make the rules, I enforce them.

He said the hardest decisions to make are the ones where a person has invested time and money into a team and for safety reasons Tomlinson must tell that guy he cant race on a given weekend.

He remembered one particularly relentless would-be competitor. This man’s father had been a drag boat racer and the man in question had built a boat about 26 feet long with a good bottom, but little freeboard and questionable construction. He showed up in Panama City, FL and, after inspecting the boat, Tomlinson told him he couldn’t run.

“You could take the steering wheel and shake the dash in both directions,” laughed Tomlinson. “His seat was a 1” by 10”pine board with some boat cushions in it.”

Then there are the unsportsmanlike conduct calls. The most recent and memorable ones were the suspensions of Jerry Gilbreath and Benny Robertson for publicly insulting APBA.

But the hardest decision is one where the conditions warrant that a race be called off. “It’s a safety decision and I have to wake up on Monday morning and look in the mirror,” said Tomlinson. “I feel the greatest responsibility is the safety of these racers. We go out and run these boats in big water and rough water and there has to be a middle ground and that’s where I come in.”

And it’s those rare moments when he loses a racer, a part of his extended family after all these years, in a fatal accident. “You always question yourself. How could I have done it differently? It’s racing and (death is) always out there,” said Tomlinson. “You hope it never comes to visit, but when it does, it’s always the same result. It’s always the same feeling.”

Looking at the last decade, Tomlinson credited Brown, Whipp and even Allweiss with putting on good events with up to 100 boats at a site. While Allweiss seems to have as many detractors as supporters, Tomlinson applauded the former APBA Offshore executive director’s approach to racing. “Michael was always dead-on in leveling the playing field. We grew. We brought in new races, we brought in new teams,” said Tomlinson.

Regardless of the organization he’s working for, it’s obvious that Tomlinson won’t change his approach to interpreting the rules of offshore racing.

“I’ve always had my integrity,” he said. “I value my integrity and it’s what I’ll leave the sport with.”

Let’s just hope he doesn’t leave too soon.

The Racing Spirit

One of the most important elements in traveling with a national racing circuit is getting to know the people involved. These amazing people come from all walks of life, diverse backgrounds, various occupations and different parts of our world and, believe me, at times we’ve wondered about the planetary origins of a few. They all, however, have one thing in common- they all seek the thrill of competitive racing. It’s not uncommon to see racers in fierce contention on the course give their equipment, assistance and support to get them back in competition after a mishap. I’m proud to be part of this community. That’s the racing spirit.

One of the most important elements in traveling with a national racing circuit is getting to know the people involved. These amazing people come from all walks of life, diverse backgrounds, various occupations and different parts of our world and, believe me, at times we’ve wondered about the planetary origins of a few. They all, however, have one thing in common- they all seek the thrill of competitive racing. It’s not uncommon to see racers in fierce contention on the course give their equipment, assistance and support to get them back in competition after a mishap. I’m proud to be part of this community. That’s the racing spirit.

As a member of the racing community, I meet the crews, the racers, and the families. I have enjoyed working with the racers and then working with their next generation of enthusiasts. Families have grown and flourished while part of the racing community. The term, family, however, also takes on a different meaning when it comes to racing. Everyone who participates or works a race becomes a member of a greater family. These people support, encourage and look out for each other. That’s the racing spirit.

I’ve learned the sport from top contenders, other officials, rescue personnel, program sellers, local volunteers, announcers, and fans. Each person in the community plays an integral role in the world of racing. Everyone has a story to tell and valuable knowledge to impart. All we have to do is listen and learn. That’s the racing spirit.

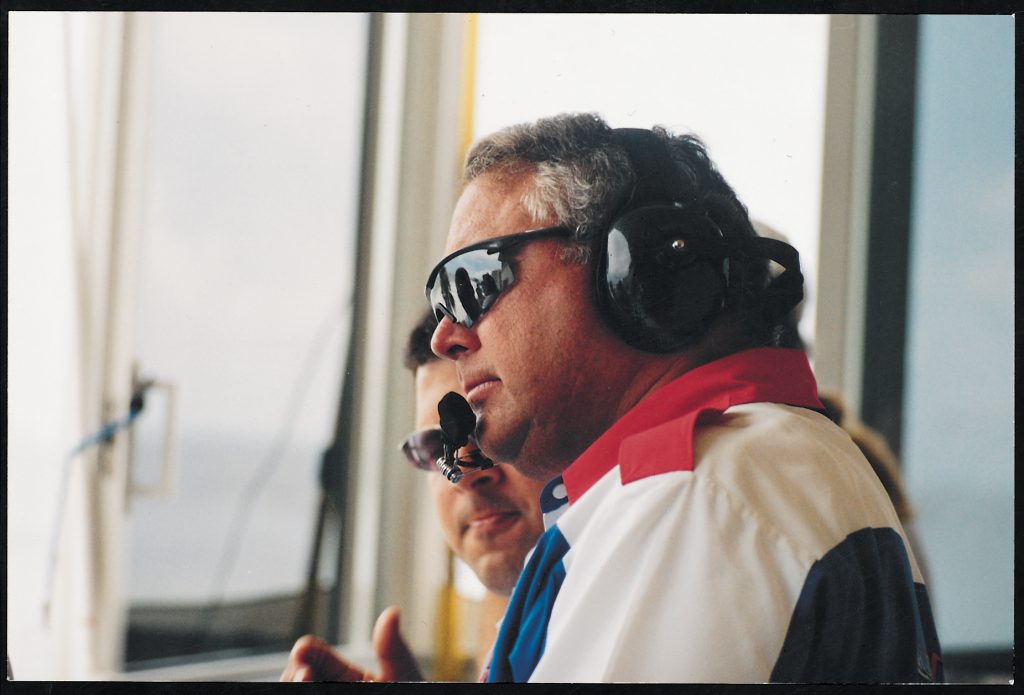

One of my greatest desires in racing is for each racer to spend at least one race on the judge’s stand with the officials to see what really takes place. I can honestly say that the race officials are the most intense, dedicated and focused people around. During stressful moments, these people can hold their breath longer than humanly possible. The Guinness world records should be notified. I have seen them shed tears of hope, agony, relief and pure joy while they continue doing their job and never miss a beat. They are true professionals who embody the racing spirit.

Racing has filled my life with friends, family, memories, excitement and valuable lessons. That’s the racing spirit. I am proud to be a part of that spirit.

-Mike Tomlinson.