There may not be anything seriously wrong when you hear that mysterious ticking sound under your boat’s engine hatch. But it really does pay to have a trained technician check it out!

By Price Turner

There’s definitely something disturbing about that mysterious and often-heard metallic ticking sound under the engine hatch. Even more so, considering it wasn’t a problem when the boat was winterized last fall! Now listen to it!

Most boaters are more than anxious to get out on the water as soon as they can, eager to take their pride and joy out of storage and have it commissioned. Sometimes, however, there’s a slight glitch – occasionally, the first time the engine is fired up. There’s a metallic ticking sound that wasn’t there before.

Advance the throttle, the ticking gets louder and faster; back off the throttle, the ticking is slower and not as loud. No warning buzzer sounded. The gauges don’t indicate any problem.

No need to panic! This is common when an engine equipped with hydraulic valve lifters hasn’t run for a while. When the engine is static (not running), the lifters that were holding valves open against spring pressure will collapse. As a result, when the engine is first started, there is slack in the valve train. As oil pressure builds in the lifters, the ticking will usually diminish and cease by the time the engine reaches operating temperature.

If this metallic ticking persists, check the oil level and appearance. When the engine was winterized, the oil and filter should have been changed; if it looks clean, it was. If your engine is equipped with hydraulic valve lifters (most are), the oil level might be low enough for a lifter to collapse without the buzzer sounding, particularly if the engine is in need of a rebuild. If the oil level is low, the simple solution is to add some more, bring it back to the proper level, and start the engine. If the ticking sound goes away, you’re all set. Chances are pretty good there’s no serious damage.

But, if after adding oil (or if the oil level was fine to begin with) the ticking persists, don’t run the engine any more than necessary. If the ticking gets louder, shut it down or things can get very expensive. (Note: Overfilling the crankcase can result in oil foaming, which causes hydraulic valve lifter bleed-down, leading to valve train clatter and loss of power and performance).

The ticking I get most concerned about is the sound that stays around, even after the engine is up and running. Occasionally, this ticking develops during the first run of the season. One (or both) of the engines suddenly begins to make tick progressively louder.

Some boaters may choose to keep running the engine, hoping the unwanted sound will eventually disappear. Wrong choice! If it didn’t go away by the time the engine reached operating temperature or commenced while the engine was running, it will most likely continue to get louder and could cause serious engine damage. The source should be determined immediately, and the problem corrected.

This problem often occurs shortly after the boat is commissioned after being in storage and is usually traced to one or a combination of the following: A collapsed lifter (if the engine is equipped with hydraulic lifters), a weak valve spring, a broken valve spring, a sticking valve or a bent valve. These five likely sources are all linked with the valve train.

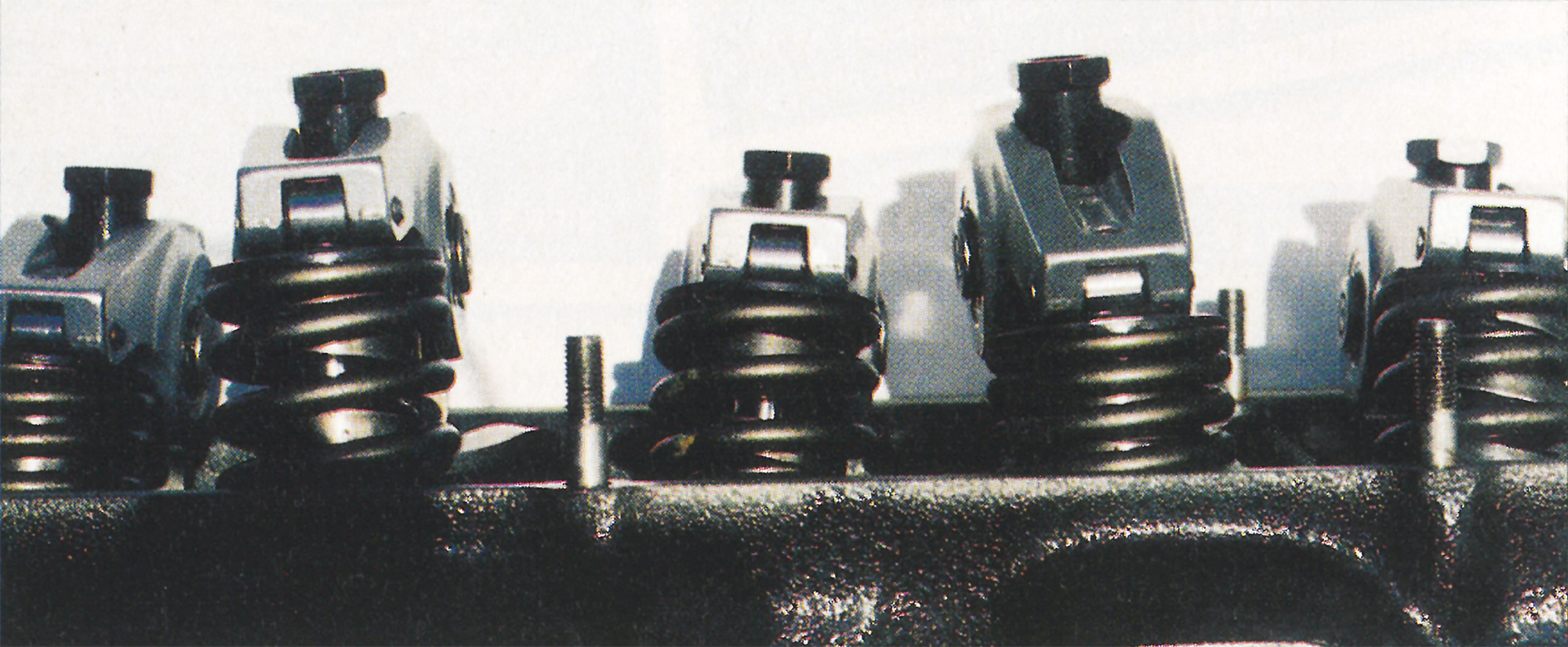

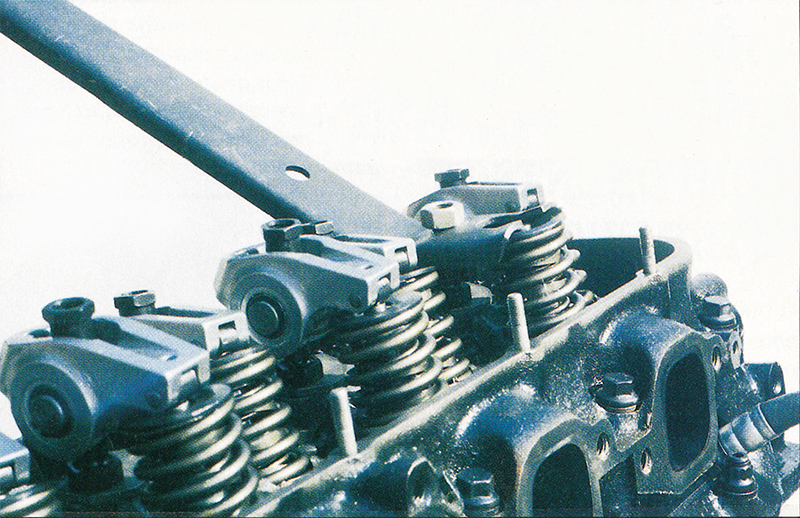

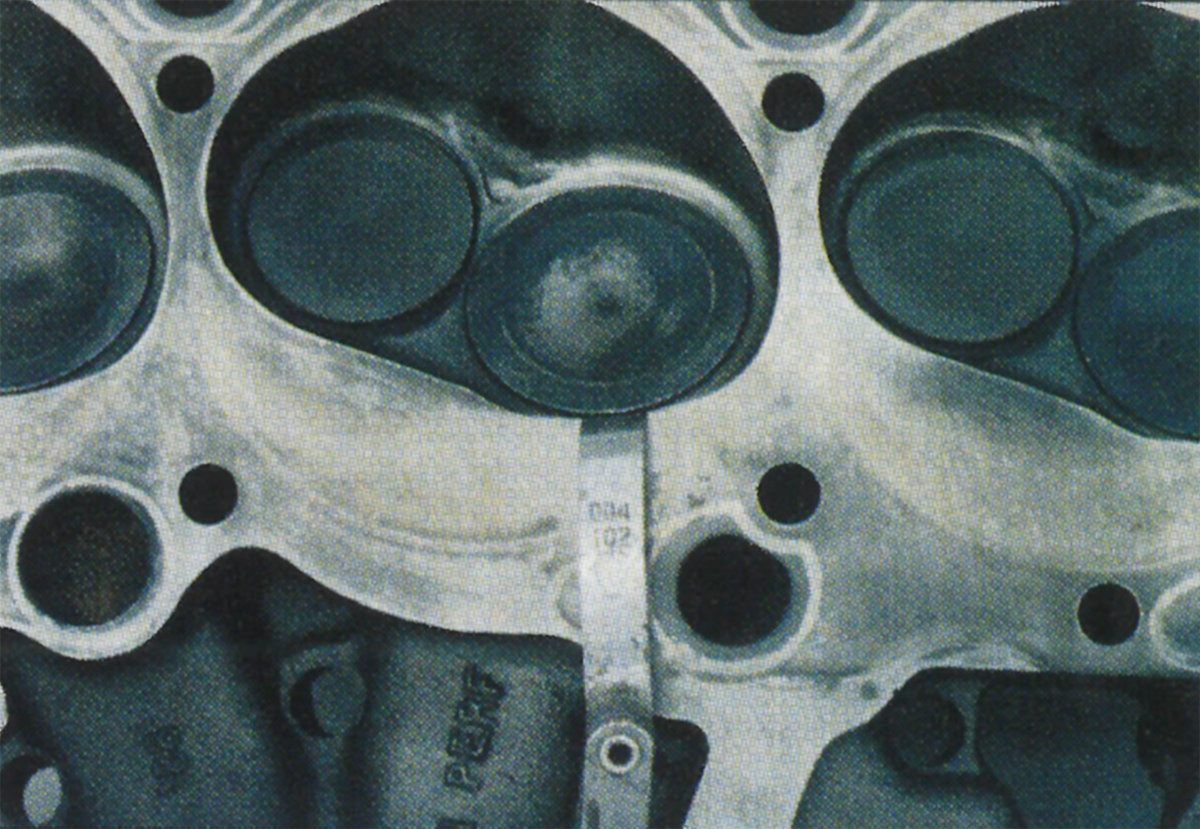

The next step is to determine which side of the engine the sound is coming from and remove the valve cover, exposing the rocker arms and valve springs.

Most engines are set up so they can be turned over without starting if the safety lanyard is disconnected. A trained technician can turn the engine over with a remote starter button while observing the visible part of the valve train.

(For the purposes of this article, I would like to define a high performance engine as any engine equipped with roller rocker arms).

WHAT TO LOOK FOR:

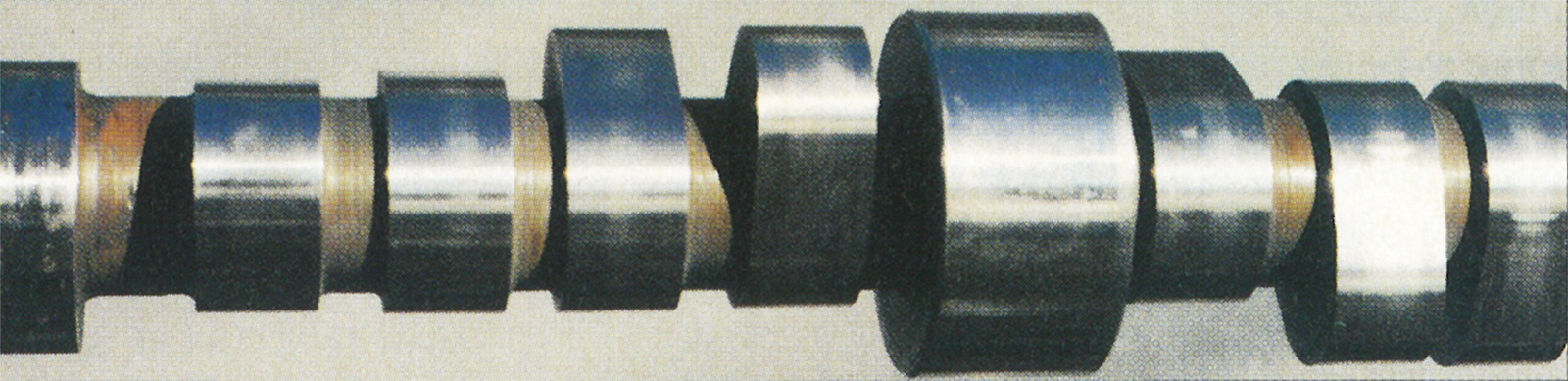

If the engine is equipped with a solid lifter cam (as used in Mercury Racing’s 900SC and other very high-performance engines) the lifters will not collapse. In this case, the springs should be checked first.

A COLLAPSED HYDRAULIC LIFTER

This can be caused by contaminated oil or normal wear. Internal tolerances are very close. A minute particle can restrict oil flow, preventing the lifter from functioning properly, thereby allowing slack in the valve train. Condensation in the crankcase (because the oil temperature is too cold, i.e. milky looking oil) can cause internal galling of hydraulic lifters. The lifters are not visible with only the valve cover removed. They are under the intake manifold, but slack in the valve train will be noticeable.

If the problem is traced to a collapsed lifter, the intake manifold will have to be removed for closer inspection, at which time most of the camshaft lobes can be inspected. Hidden lobes can be checked for proper lift with a dial indicator. If the cam is worn it must be replaced and new lifters installed. If there’s no problem with the hydraulic roller cam and one or more lifters are bad they should all be replaced. If the engine is not equipped with roller lifters and any lifters are bad, both cam and lifters must be replaced.

THE VALVE SPRINGS ARE ONE OF THE MOST CRITICAL AND MOST OVERLOOKED COMPONENTS IN THE ENGINE

At 5000 rpm, each spring must cycle more than 2500 times per minute. The tremendous heat generated by this stress effects the heat-treating and eventually causes a drop in pressure.

What’s more, all the time the engine is not running some of the springs are compressed. Although this doesn’t build heat it is a strain on the springs and valve train. It is unnecessary and not advisable for the valve springs on high performance engines to be left under tension when the engine is not going to be run for several months.

Most conscientious weekend racers relieve the valve spring tension after the last race of the weekend. You say your boat isn’t powered by a racing engine? Truth is, some high-performance boat engines are close to being race engines, and in fact some are race engines.

Given the improvements in metallurgy and engine technology over the past few years, relieving spring pressure after the weekend may not be necessary. But the simple truth is, if the boat is not going to be used for an extended period of time (e.g. in winter), it should definitely be considered.

Don’t just take my word for it! This procedure is also highly recommended by Mark’ Campbell, Director of Research and Development for Crane Cams, Ron Iskenderian, Isky Racing Cams Engineer and Jay Adams, Comp Cams Technical Consultant.

The more radical the cam and the heavier the valve train, as in hydraulic roller lifters, the greater the spring pressure required to pre-load the valve train and the greater the importance of relieving the pressure. With the valve on the seat there is no stress on the valve train. Spring pressure is confined between the valve spring seat and valve spring retainer.

Seated valve spring pressure is approximately one third valve open spring pressure. For example, spring pressure specifications for the popular Mercury Racing HP500 engine are: valve closed (on seat) 150 pounds, valve open (full lift) 420 pounds. That’s a lot of pressure to leave on the valve train for several months. As you can see in this particular engine, compressed spring pressure will vary anywhere from 150 pounds to 420 pounds all the time the engine is not in use. When the springs are left compressed, the oil film between the pressure points of the valve train breaks down. Then, when the engine is started, there is momentary metal-to- metal contact in those areas until the oil pump builds pressure.

A WEAK VALVE SPRING

A spring left compressed for a long period of time has a tendency to relax and lose some of its energy, shortening its useful life and leading to an unstable valve train. Valve spring pressure must be adequate to force the valve train to follow the cam profile, keep the valves from bouncing on the seat when they close, seal the combustion chambers and prevent spring surge.

As the cam turns, the lifter rides up the opening flank of the lobe, opening the valve through the linkage against spring pressure at the valve. The lifter then goes over the nose of the lobe and down the closing flank. Here is where the problem arises.

If the valve spring is weak, lofting occurs. The lifter loses contact with the cam lobe, allowing slack in the valve train. When the lifter comes in contact with the lobe again the slack is taken up and there is a ticking sound.

The valve train can’t tolerate such abuse for long. This also damages the lifter and causes chatter marks on the cam lobe. When valve springs are weak, valve float occurs at a lower rpm than normal .

Valve float is when valve train components fail to follow the dictates of the cam profile. Under this condition, the valve is a greater distance off its seat than normal, causing a loss in compression and power as well as possible engine damage if the floating valve strikes the oncoming piston.

In supercharged engines, intake valve springs must have more seat pressure than exhausts. Depending on boost and the diameter of the intake valve, the pressure on the back of the intake valve can be 30 to 60 pounds. Subtract this from the standard minimum seat pressure and the reason is obvious. This is only one reason why simply bolting a supercharger to an otherwise stock engine is not advisable.

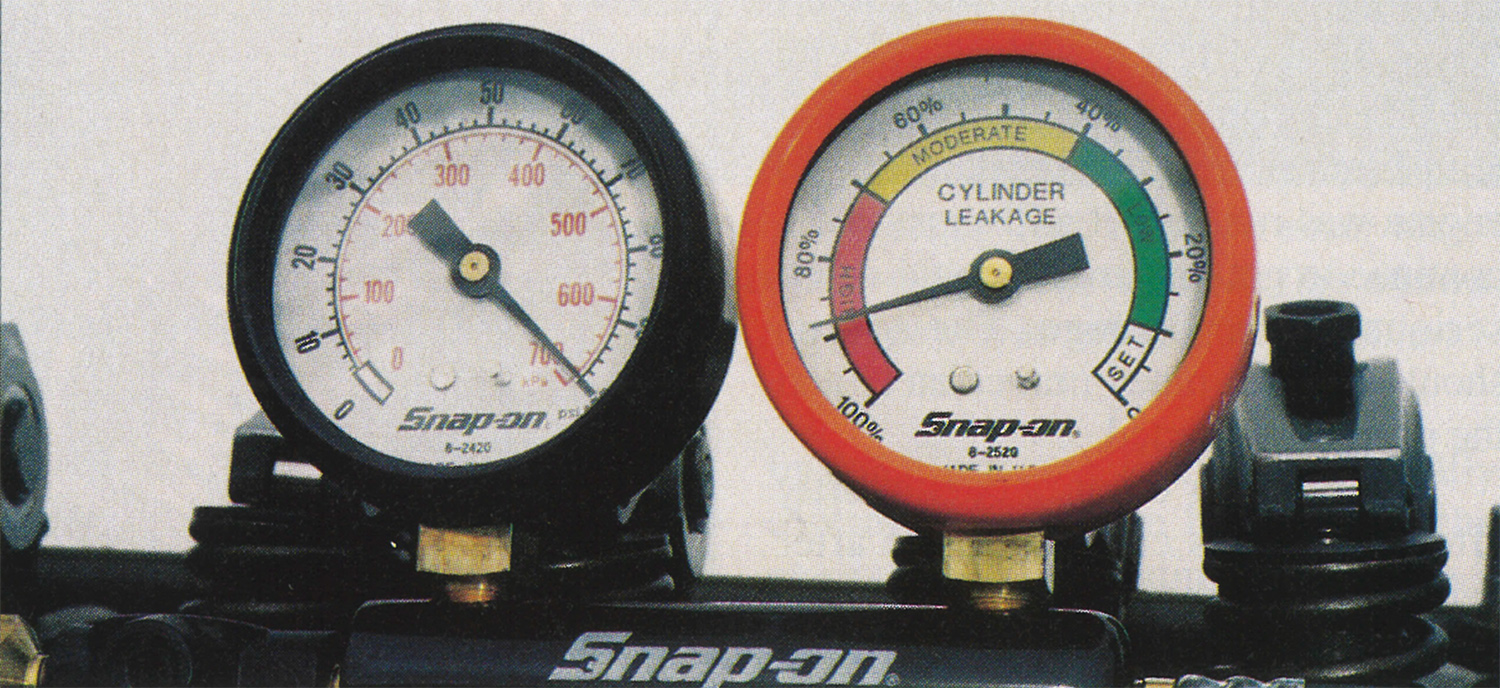

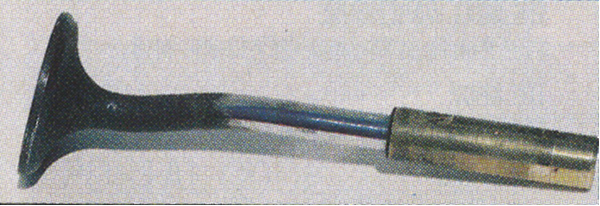

Weak springs may not be readily noticeable, but they can be checked with a seat pressure tester without removing the head. Springs should be replaced if not within 10 pounds of specified tension; it is an indication they are fatigued.

Springs can be replaced without dismantling the engine using special tools for that purpose.

A BROKEN VALVE SPRING

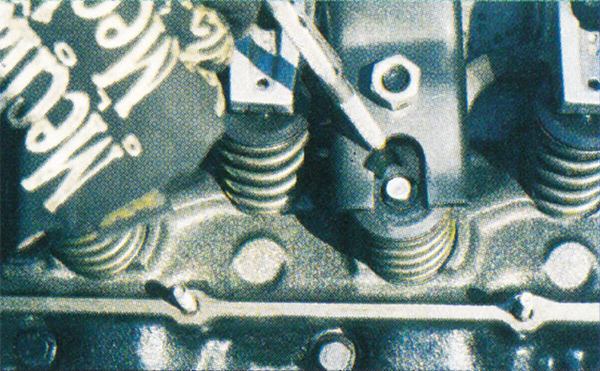

If a spring is broken near the tip or bottom the symptoms will be similar to that of a weak spring. But if the spring is broken near the middle the valve could drop down far enough to come in contact with the piston, possibly being bent or even broken, causing serious engine damage. Or, if there is enough slack in the valve train, the pushrod can come out of the cup in the rocker arm and the valve will no longer be actuated. This also is readily noticeable.

If a spring is broken near the tip or bottom the symptoms will be similar to that of a weak spring. But if the spring is broken near the middle the valve could drop down far enough to come in contact with the piston, possibly being bent or even broken, causing serious engine damage. Or, if there is enough slack in the valve train, the pushrod can come out of the cup in the rocker arm and the valve will no longer be actuated. This also is readily noticeable.

A cylinder leakage test will determine if a valve is bent or sticking partially open in the guide. When the cylinder is pressurized, the technician will usually be able to hear air escaping either through the intake or exhaust and thereby locate the problem.

A broken spring can be replaced without removing the head but if a valve is bent the cylinder head must be removed and the valve replaced.

A STICKING VALVE

Usually an exhaust valve. In high performance engines the exhaust valve stem seal is not as tight as the intake valve stem seal. The exhaust valves get much hotter than the intakes requiring slightly more stem lubrication to prevent galling (clearance is only one to three thousandths of an inch). Hot exhaust gases flowing across the exhaust valve bake the oil and residue from the combustion process on the valve stem, forming a build up when the engine is running.

Most boats are stored in unheated buildings or outside. Constant temperature changes create condensation. The exhaust pipes are usually open to the elements all winter. Flappers on the exhaust don’t seal tight. Even though t e engine was fogged in preparation to storage, there is little if any oil residue on exhaust valves because they are hot when the engine is running. If the valves are left off their seat (open) the combustion chamber is exposed to the environment, inviting rust and corrosion – particularly if the boat has been used in salt water.

These conditions, combined with the build-up on the exhaust valve stem (mentioned above) and a weak spring, can cause the valve stem to wedge in the guide instead of closing, and lead to a sticking valve.

Once a valve has failed to seat properly, combustion gases are forced between the valve and seat and they begin to erode, leading to loss of compression and power. If this is the case, adjusting the valves to eliminate the ticking is not the solution to the problem, because as the engine is run (if the build up on the stem wears away or the valve guide wears) the valve will be held off its seat by the adjustment that eliminated the ticking, again allowing combustion gases to leak past, possibly creating all the problems mentioned earlier.

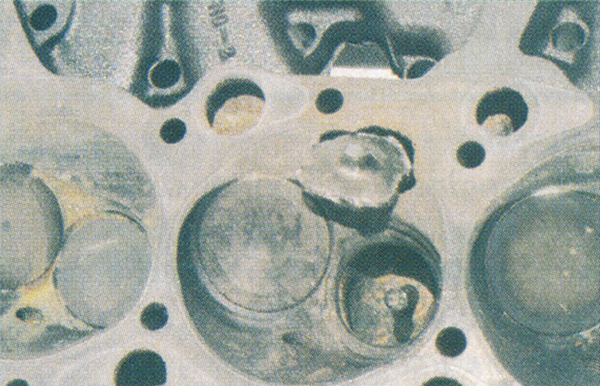

A BENT VALVE

Occurs when a valve comes in contact with a piston, either because of a weak spring, a broken spring as mentioned above or the valve stuck open far enough to contact the piston. If a valve is bent the cylinder head must be removed and the valve replaced.

STRESS RELIEF FOR THE VALVE TRAIN

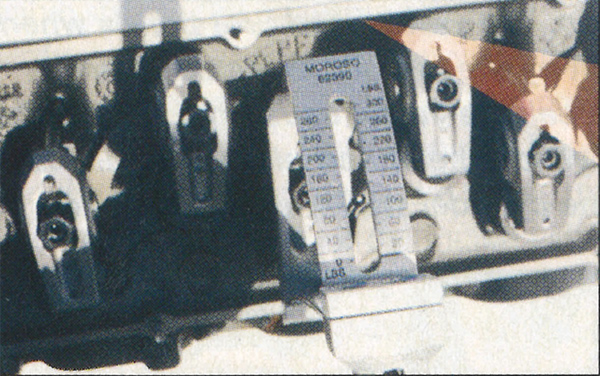

The procedure for relieving spring tension: After the engine is fogged the crankshaft is turned manually to the number one firing position. The rocker arm adjusters that are compressed are backed off until all valves are on their seats.

This relieves the spring pressure considerably. It’s very cheap insurance against sticking valves and weakened or broken springs.

A tag must be attached in a highly visible location, indicating which rockers were backed off in the event someone else commissions the boat in the spring.

Valve train problems have almost been totally eliminated in engines we have performed this on. Of course, those rocker arms that were backed off will have to be readjusted before the engine is run. On GM Mark IV, Gen V, and VI engines this is done by manually turning the crank shaft 360 degrees. Affirm that the pushrod is seated in the socket on the underside of rocker arm and adjust the rocker arms that were backed off to the specifications for that particular engine.

A gradual loss of spring tension is similar to a governor limiting engine rpm. This loss of rpm can’t be recovered through a tune-up or carburetor rebuild, nor is it likely to be detected by compression check or cylinder leakage test. It’s caused by the valves floating or bouncing on their seats at high rpm.

So if your engine is sluggish and you have done everything to regain the lost power without success, it might be time to have the valve springs checked. It’s much cheaper than repowering. There is no way of knowing how many engines are handicapped by weak valve springs, but they show up eventually!